AMERICA HAS A PATRON SAINT, A FEAST DAY AND A BAPTISMAL CERTIFICATE

Dr. Sándor Balogh

Saint Imre > Amerigo

America as a continent and the United States of America as a country are unique in that they had been named after a saint.

Everyone knows that America was named after Amerigo Vespucci, but who was Amerigo named after?

Very few people know this; at least, very few Hungarians and Italians know this. I, for one, have never heard Hungarians, particularly Hungarian Catholics, say that they are proud of the fact that America, after Amerigo Vespucci, was named after the Hungarian Saint Imre (Emeric). Therefore, America’s name-day is November 5th, the feast-day of Saint Imre.

I, too, was greatly surprised to read that Imre was the original name-giver of America. In one of the newspapers in America, there was a section that published little-known interesting facts, under the title: Believe It or Not! They had received from Father Claude Klarkowsky, a Polish priest from Chicago and amateur genealogist, this surprising information: Ripley’sBelieve It or Not! “The Hungarian Prince who gave America its name – The name given the New World by mapmaker Martin Waldseemüller in 1507 was derived from Amerigo Vespucci the Florentine navigator who was named Amerigo after Saint Emeric, son of the first Christian king of Hungary.” (10/11/80)

At first, I was among those who did not believe this, or at least doubted it. So, based on the information from Father Klarkowszky, I wrote a short letter to the local Catholic newspaper, The Evangelist. They published the letter and, a few days later, I received a telephone call from a local priest who had read my letter.

He began by saying that, initially, he too had received this news with skepticism, because „those Eastern European immigrants think that they had discovered everything.” But then he looked into the Church History book that he had used at the seminary, and behold, word for word, he found the following:

HUNGARY … “Szent István (Saint Stephen), the founder of the Hungarian state, died on August 15, 1038. To his misfortune, his only son, Saint Imre, the patron saint of Amerigo Vespucci, and consequently of America, died in a hunting accident.” (A Summary of Catholic History, Volume I Ancient & Medieval History, By Newman C Eberhardt, C. M; Herder Book Co; St. Louis 2, MO. p. 538; my emphasis)

Encouraged by this, I published the story in the still-existing weekly newspaper, MAGYAR KATOLIKUS VASÁRNAP, and I received another letter. Dr Miklós Horváth, a priest and professor at the Catholic John Carroll University, sent me a clipping from an issue of Our Sunday Visitor, from 1931, in which Bishop John Noll of the Fort Wayne Diocese, wrote:

„Saint Imre (Emeric) took a vow of celibacy. The fact that this young man faithfully kept his vow, even during four years of marriage, and became a spiritual example to a people recently converted to Christianity, caused the memory of Saint Imre to be held in such high regard that it would be difficult to find its equal in the history of man. His popularity grew and he became the patron-saint of European youth under the name of Sanctus Emericus or Americus. When Amerigo, to be the heavenly patron of his third son, and therefore, he called his son Amerigo. Thus Hungary can be seen to be the name-giver of America.”

Another letter-writer sent a newspaper clipping in which Dr. Howard V. Harper poses the question: From where did America get her name? Then he answers it: „Intelligent scholars answer that America got her name from the 16th century discoverer, Amerigo Vespucci.This is of course very true. Imre is Emericus in Latin and the Italian form is Amerigo. Thus, with a linguistic leap, America is named after Saint Imre.” (Acron Beacon Journal, Nov. 3, 1962).

Msgr. György Pap published in the December, 1968 issue of the Magyar Kultúra a photograph of the triptych of the main altar of the Settignano St, Martino a Mensola chapel, near Florence, which was painted in 1391, On it can be seen a man, holding a white lily, the symbol of virginity, representing Amerigo D’Ungueria. I was later successful in obtaining a photograph of the center-piece of the triptych, the three part altar painting, thanks to Maria Prokopp, a Hungarian art historian. The painting shows the Virgin Mary, with the baby Jesus on her arm, surrounded by two saints, Saint Julian and Saint Emerich of Hungary, with the patron of the chapel and the painting, Amerigo Zati, kneeling in front of her.

Triptych of main altar, S. Martino a Mensola, by Francesco di Michele

Inscription:

left wing SCA MARA MADALENA SCO NICCHOLO SCA CHATERINA,

center SCO GIULIANO SCO AMERIGHO D UNGHERIA MCCCLXXXXI OTTOBRE

ight wing SCO MARTINO SCO GHIRIGORO PAPA SCO ANTONIO ABATE

The center piece

Thus it is obvious that the businessman inserted his own name-giver and patron-saint into the painting, so the connection between the names Amerigo and Imre (Emeric) is undeniable. The other saint, Guiliano, is the patron-saint of Amerigo Zati’s brother, Julian. On the two wings the patron saints of Zati’s children can be seen.

From this it is clear that it was not the altar-piece that caused the name Amerigo to become widespread, but the name had been used for a long time and it was well-known who Szent Imre was, at least around Florence, so this explains the triptych.

Thus the connection between Amerigo and Saint Emeric can be indisputably documented. Let us now examine the connection between Amerigo and America.

Amerigo > America

Everyone knows that Columbus discovered America. But he did not know what he had discovered; that is, he thought that he had found a shorter route to India and that is why he named the indigenous people Indians.

Vespucci was the one who realized that this was not India, but a “New World”, and an ocean separated it from India. His report about this circulated among the European scholars. Since this scientific discovery was made by Vespucci, when the editors of the map collection called: Cosmographiae Introductio, among them Martin Waldseemüller, decided that the name „New World” did not sound appropriate for the name of a continent, they decided to call the continent that had been nameless until that time, after Amerigo Vespucci. Martin Waldseemüller, after he had explained the origin of the name in the text that accompanied it, stated that „he did not see that anyone would have any reason to object to it!”

The derivation of the name is easily followed: Imre>Emericus>Amerigo>America. So, in the name “America” one finds traces of both the Latin name Emericus, and its Italian version, Amerigo. Since, in those languages, which assign gender to objects (like Latin or Italian), geographical names are always designated as the feminine gender and regularly end in “a”, from Amerigo and Emericus, instead of the masculine Americus we find America, ending in the feminine “a”.

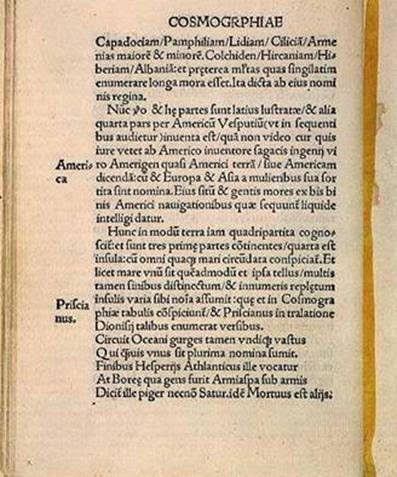

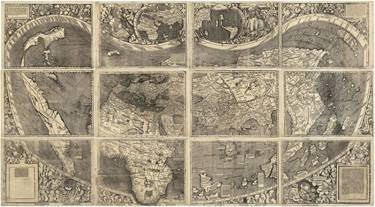

Some scholars consider Waldseemüller’s map and the Latin document presented below, in which Waldseemüller renders only documented account of the naming of America, to be the Baptismal Certificate of America. It says “… The fourth part of the world, since Americus discovered it, ‘Amerigen’ (In Greek ‘gen’ = land) i. e. ‘Americus land,’ as well America could be called” (p. 25) On another page of the Cosmographiae Introductio, we read, “But now these parts [Europe, Asia and Africa, the three continents of the Ptolemaic geography] have been extensively explored and a fourth “part” has been discovered by Americus Vespuccius as will be seen in the appendix: I do not see what right any one would have to object to calling this part after Americus, who discovered it and who is a man of intelligence, [and so to name it] Amerige, that is, the Land of Americus, or America: since both Europa and Asia got their names from women.” (http://www.uhmc.sunysb.edu/

Waldseemüller’s original map from 1507,

Originally the name America referred only to SOUTH AMERICA, and only in 1538 did the famous geographical expert, Gerard Mercator, apply it to the northern part of the continent.

Although there are earlier maps (e.g. Cantino World Map in 1502) which appear to differentiate the newly discovered land from India, Waldseemüller’s map was the first to show an ocean in between India and America. At the same time, Waldseemüller was the first to use the name America. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

The full name of the map: „Universalis cosmographia secundum Ptholomaei traditionem et Americi Vespucii aliorumque lustrationes”, that is: Universal World Map according to the tradition of Ptolomeus, and the discoveries of Amerigo Vespucci and others.

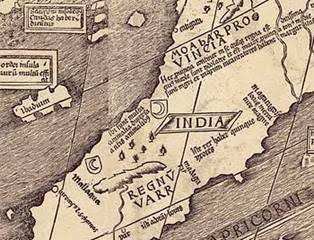

Detail of the map showing the name “India,” on the Asian continent

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

This wall map is comprised of 12 rectangular sections of 18 by 24.5 inches, and the only currently known copy was purchased for $10 M, and is displayed in the Library of Congress.

Vespucci’s book: Mundus Novis, that is New World, published in 1504, was distributed widely and in it he stated that the newly discovered land was a new continent. This influenced Waldseemüller too. It is interesting to speculate how Vespucci came on the idea that the New World was another continent and why Waldseemüller found Vespucci’s discovery so convincing. Peter Whitfield, a historian, suggests that Vespucci saw that the indigenous people were neither of the Indian nor of the Chinese race (same source), and measuring longitudes, he found that therefore there must be an ocean dividing India from the New World.

Professor JONATHAN COHEN at SUNY Stony Brook after documenting the Waldseemüller explanation, list several theories that are without any proof or documentation, and concludes by referring to the current (fourth) edition of Webster’s New World College Dictionary that „admits the mystery that surrounds the origin of the name America.”

Then adds his own opinion or rather, conclusion: „No definitive conclusions can be reached. Too many claims are, for lack of hard evidence, based on speculation. Theories about the true origin of the name are ultimately historical fictions, whose authors are inclined to impose their own political, cultural, or national agendas on the name and its origin. Yet behind these fictions lie compelling views of the New World. Taken together, they form a multicultural vision of its distinctive character. To hear Americus in the name; to hear the Amerrique Mountains and their perpetual wind; to hear the African in the Mayan iq’ amaq’el; to hear the Scandinavian Ommerike, as well as Amteric, and the Algonquin Em-erika; to hear Saint Emeric of Hungary; to hear Amalrich, the Gothic lord of the work ethic; to hear Armorica, the ancient Gaulish name meaning place by the sea; and to hear the English official, Amerike — to hear such echoes in the name of our hemisphere is to hear ourselves.”

It is unfortunate that those intelligent people who were trying to explain the name America, were looking for explanation everywhere except in Florence, Vespucci’s home town. Even Prof. Cohen, who wrote that “The naming of America, then, becomes essential to a full understanding of our history and cultural values — ourselves — especially when considered in terms of the range of theories about the origin of the name,” fails to look there. If he did, he would have found the missing link between Imre and Amerigo. Instead, he also claimed that “no proof of this etymology exists.” (http://www.uhmc.sunysb.edu/

So, in our multi-ethnic, multi-cultural society, everybody wants to share the glory, but only two connections are documented: az Imre-Amerigo through the altar painting in Florence, and the Amerigo-America link by Waldseemüller’s own words. These theories have been developed before the Imre-Amerigo-America link has been documented by the 1391 altar painting, but let us not overlook an important point. Others may have found “something,” and may even found a name that sounded like America, but it was Amerigo Vespucci who discovered that it was a NEW continent! Nobody can take it away from him!

Yet, as with many important discoveries, there are still some doubting Thomases of this obvious and well documented explanation also. Some tried to raise doubts, and want to deny the Italians the well deserved honor of having America named after an Italian, or the Hungarians for giving Saint Imre to the world, after whom Amerigo was named.

The best summary of this discussion was made by Heinrich Charles, who was quoted by Zoltán Farkas in an article (The Challenge of the Name America, NAMES VOLUME 13 . NUMBER 1 . MARCH 1965), analyzing in great detail the various theories of the origin of the Amerigo name. According to Charles it is interesting to read these “fantastic stories and theories” about the name America “as long as the facts of the naming of the New World were unknown.” But once one knows the facts, these theories look silly.

One can assume that the doubters of the origin of the Amerigo name were not aware of the altar painting in a small, obscure Italian church, but it takes gall to doubt Waldseemüller’s declaration about naming the New Continent after Amerigo Vespucci.

MVSZ Sajtószolgálat

8405it/211105